25/03/2019

Robot arms made of shape memory wire

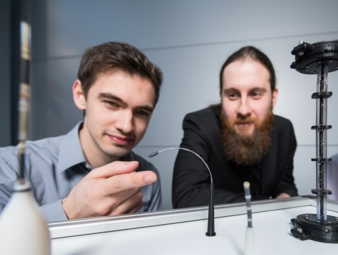

They snake as precisely as freely in all corners and directions. Flexible robot arms, such as those developed by Stefan Seelecke and his research group at German Saarland University, do not have more or less stiff joints, but rather “muscles” made of metals with shape memory.

The joints of human and robotic arms are often rather bulky and connect rigid bones or mechanical assemblies. Motion is typically restricted to certain spatial directions. In contrast, an elephant’s trunk or an octopus’s tentacle offer far greater agility. The presence of tens of thousands of muscles enables these creatures to move the trunk or tentacle in all directions, to bend it to just the right degree and to grip things with great power. The engineers at Saarland University have drawn inspiration from these natural models. They are developing robotic arms that do away with the need for joints or rigid skeletons or frameworks, creating structures that are both lightweight and extremely supple.

Stefan Seelecke and his team are collaborating with researchers from Darmstadt Technical University on a project funded by the German Research Foundation DFG in which they are developing thin, precisely controlled artificial tentacles. In future, the system could find use as a guide wire in cardiac surgery or as an endoscope in gastroscopic and colonoscopic procedures. The researchers are therefore equipping the artificial tentacles with additional functions such as a gripper or a tip with adjustable stiffness that delivers an improved pushing force. But the technology can also be scaled up successfully to produce large robotic arms not dissimilar to an elephant’s trunk.

The flexibility of these new robotic arms comes from the artificial “muscles” used by the Saarbrucken research team. These muscles are composed of ultrafine nickel-titanium wires that are able to contract and lengthen in a controlled manner. The ultrafine nitinol wires contract like real muscles, depending on whether an electric current is flowing or not. Seelecke explains: “Nickel-titanium is a shape memory alloy. It’s able to remember its shape and to return to that original shape after it being deformed. If an electric current flows through a nitinol wire, the material heats up, causing it to adopt a different crystal structure with the result that the wire becomes shorter. If the current is switched off, the wire cools down and lengthens again."

His team at the Intelligent Material Systems Lab at Saarland University create bundles of these wires that act as artificial muscle fibres. ‘Multiple ultrathin wires provide a large surface area through which they can transfer heat, which means they contract more rapidly. The wires have the highest energy density of all known drive mechanisms. And they can exert a very high tensile force over a short distance,’ explains Seelecke, who also conducts research at the Centre for Mechatronics and Automation Technology in Saarbrucken. The research team is developing a range of applications for these wires, from novel cooling systems to new types of valves and pumps.

For the robot arms, the researchers link the wire bundles so that they act as flexor or extensor muscles, which when they work in concert produce a flowing motion. “The tentacles that could be used in future as medical catheters or in endoscopic procedures have diameters of only around 300µm to 400µm. No other drive system is of comparable size. Previous systems used for catheter procedures were significantly larger and this tended to limit their capabilities”, explains Paul Motzki, who wrote his doctoral thesis on the shape memory wires and is a research assistant in Professor Seelecke’ s team.

The new tentacles can be very precisely controlled and can be used to create multifunctional tools. For example, the distal tip of the tentacle can be made to perform a pushing movement. The exact pattern of movement required is modeled by the researchers and then programed on a semiconductor chip. And the system has no need for other sensors. The wires themselves provide all the necessary data. “The material from which the wires are made has sensory properties. The controller unit is able to interpret the electrical resistance data so that it knows the exact position and orientation of the wires at any one time”, reports Motzki. Unlike conventional robotic arms that require power from an electric motor or from a pneumatic or hydraulic system, the arms being developed in Saarbrucken have no need for any such heavy equipment. All the wires need is electric current. “This makes the system light, highly adaptable and quiet to operate, and it means that production costs are relatively low”, says Professor Seelecke.

University Saarland

Chair of Intelligent Materials Systems (IMSL)

Contact person is Mr. Stefan Seelecke

Tel.: +49 681 302-0